Alice in Wonderland Syndrome

- Aprajita Karki

- Nov 26, 2020

- 5 min read

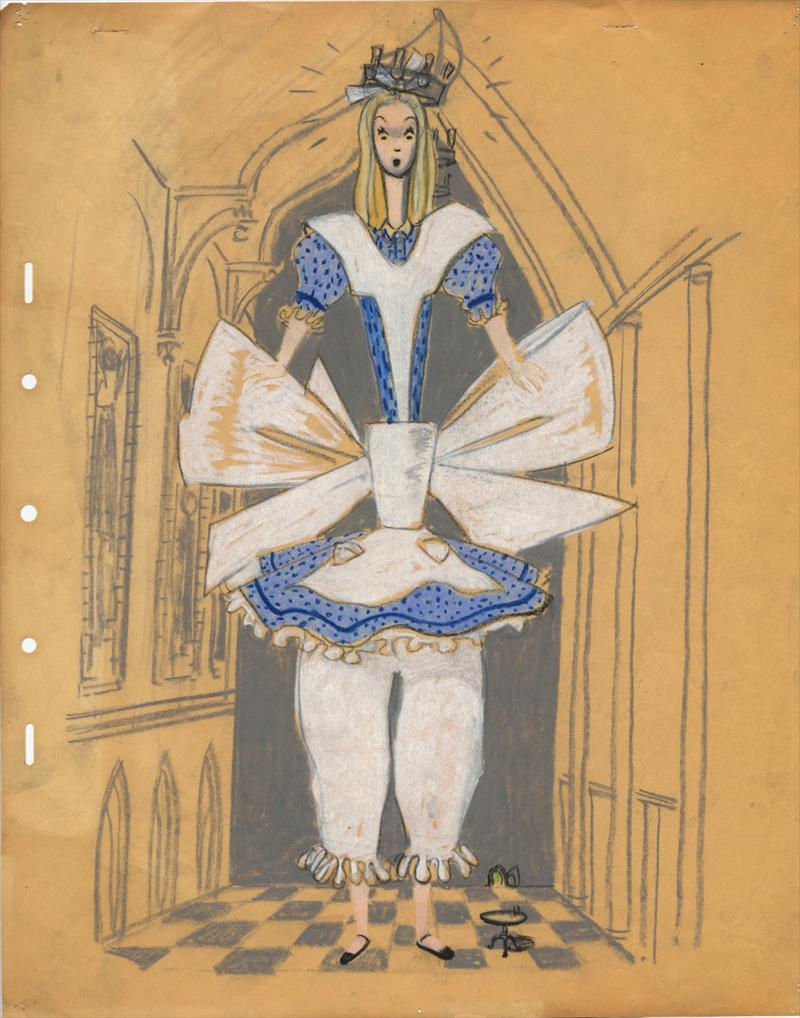

The story of Alice in Wonderland portrays many characters with peculiar behaviours and mannerism. Understandably, these narratives are tailored according to cognitive comfort of the children. Whereby the dialogues are delivered in a vague yet directional way: Mad Hatter: “Have I gone mad?” Alice: “I’m afraid so. You’re entirely bonkers. But I’ll tell you a secret. All the best people are.” Statements such as these help the audience understand that it is alright being different, and sometimes this peculiarity may be a strength. Alice in Wonderland is so infused with mental health dialogues that it has a syndrome named after it: Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS).

Many are interested in the relationship between mental health concerns and art based on the speculation that the art created may be inspired by the mental illness. Well, known artists such as Lewis Carroll and Picasso have disclosed experiencing migraines. Researchers believe that their works could have been influenced by these migraine-like features. The role of migraine is well defined in Carroll’s work. It can be traced back to his own personal diaries, where he mentions odd optical effects followed by headaches. In his family journal, he published a figurative representation with the right side of his face, shoulder and hand erased. This directly gives an insight into the symptoms of AIWS, where an individual perceives the self in distorted ways. This syndrome was first discussed by Caro Lippman in 1952. However, it was defined by John Todd in 1955, which became more influential. For this reason, the syndrome is also called the ‘Todd’s Syndrome’. Todd reported six cases of AIWS during his research, all of whom had perceived body distortions similar to Alice as a character.

AIWS is a complex neurological disorder believed to be transmitted genetically where an individual perceives an altered body image. They also have a distorted perception of time, touch, sound and visuals. There are many examples of such distortions in Call’s literary work itself. Alice experiences a strange feeling while going down the rabbit hole: “Either the well was bottomless, or she fell very slowly. Since she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next”. Here Alice cannot ascertain the depth of the hole or the time involved. Another instance of a seeming distortion is when her body shrinks after consuming a drink labelled “Drink Me”. Next, when she eats a cake following which she becomes large enough to touch the ceiling. There are some statements in the book which also indicate towards depersonalization which is also an essential indication of the syndrome, “I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I’m not the same, the next question is, who in the world am I?”. However, in the subsequent books, Alice mentions feeling body acceleration without achieving distance. These descriptions give a curious take on the possible influence of the author’s own condition on his work.

People who have this syndrome get chronic headaches or migraine pain; experience temporal lobe induced epilepsy and sometimes carry viruses from the herpes family, which induce specific symptoms. The main symptom remains a migraine-like condition that often occurs before and/or after the perceptual distortion episode. It is crucial here to mention that a person who lives with AIWS does not experience hallucinations. However, the distortions in perceptions may be so severe that they become borderline hallucinations. For most people, these perceptual distortions last a few minutes. Some account seeing changing hair colours on people, colours floating around or lingering, an opaque shadow following behind people like a trail. Even a camera flash may have an afterimage lasting up to an hour. Bizarre, borderline hallucinations such as raining inside the room through the ceiling have been accounted for by some. The syndrome has been characterized only by distortions, people also report psychosis with ‘soft visual hallucinations’ alongside, such as walls breathing in and out. At the same time, random colourful shapes float in front of their eyes.

Central distortions experienced by the person with AIWS make the general shape and size of objects/people around look disproportionate. This is not limited to the external world and extends to the perception of self too. The visual distortions can be of four times: Micropsia (objects appearing small), Macropsia (objects appearing large), Pelopsia (objects appearing to be closer than they are), Teleopsia (objects appearing to be further away than they are).

The mechanism involved in the proper development of the internal-external relationship is affected negatively. Hence, it also deregulates the way someone perceives their body image. Todd found out that all people with AIWS had a distorted body perception with some reporting visual perceptual disturbances. Thus, the diagnosis of AIWS based solely on visual disturbances can be misleading and must be accompanied by self-perceived distortions in body size, shape or form. They may see themselves to be bigger than their bed or may feel they are too tiny for their clothes which hang off their body. Regardless to mention, these distortions make it difficult to function in daily life. One person narrates perceiving her teeth to be ten times bigger than her mouth. Unfortunately, this syndrome has no treatment yet and is often misdiagnosed. While most children exhibit this syndrome, it is rarely present in the elderly. Among every 100 children, this syndrome is found in 4 and seems to have more effect at the night time. Surprisingly, while watching the movie ‘Alice in Wonderland’ children with AIWS feel the exact same happening to them in real life.

Undoubtedly people who live with this syndrome find it difficult many times, but some put a twist on the way they view things. They compliment their partner’s head when they see a different colour on it or appreciate different coloured dots on their cats. They may tell their friends they look funny with a head more significant than their body. Humour, acceptance with the ability to view their visual disturbances as a way to give new meaning to their reality has helped many.

References

Dey, A. (2018). Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AWS). https://medsphere.wordpress.com/2018/12/06/aiws/

Fitzgerald, L. (2016). Alice in Wonderland Syndrome. https://prezi.com/svrhwadkr5ms/alice-in-wonderland-syndrome/

Lanska, D. J., & Lanska, J. R. (2018). The Alice-in-Wonderland Syndrome. In Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience (Vol. 42, pp. 142–150). S. Karger AG. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475722

Mastria, G., Mancini, V., Viganò, A., & Di Piero, V. (2016). Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A Clinical and Pathophysiological Review. In BioMed Research International (Vol. 2016).

Hindawi Limited. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8243145

Miclau, K. (2017). De-stigmatizing Mental Illness Early: Role of Childhood Animations. https://www.hcs.harvard.edu/~hcht/blog/de-stigmatizing-mental-illness-early-role-of-childhood-animations

Scott, A. (2016). What it’s like to have Alice in Wonderland Syndrome as an adult. https://metro.co.uk/2016/06/16/what-its-like-to-have-alice-in-wonderland-syndrome-5949155/

Comments